Fantastic Planet (1973) (French: La Planète sauvage). Directed by René Laloux. Written by René Laloux and Roland Topor. Starring Jean Valmont, Jennifer Drake, Eric Baugin, Jean Topart.

Roland Topor was just three years old when his father was arrested by the Gestapo. Topor’s parents were Polish Jews who had left Poland for Paris a few years before. After the 1940 Nazi invasion of France and establishment of the fascist Vichy government, thousands of Jewish men were arrested and transported to prison camps. Roland’s father, Abram, was sent to Pithiviers, a camp where prisoners were held before being transported to Auschwitz.

But Abram was able to escape and go into hiding. The Gestapo searched for him, and that included having the Topors’ landlady interrogate Roland and his older sister about their father’s whereabouts. The landlady was unsuccessful, the Gestapo were unsuccessful, and soon the entire family fled Paris. Roland was placed with a Catholic family in the Savoy region of western France for protection.

The Topor family were among the fortunate ones. After the war was over, they returned to Paris and successfully sued to have their belongings and their home returned to them. That meant they moved back into the apartment with the same landlord who had tried to sell them out to the Nazis just a few years before.

Roland Topor would grow up to study art at Beaux-arts de Paris, and in the late ’50s he began to work as an illustrator for French magazines. His illustration work tended to be simple, striking, and exceptionally weird line drawings, where a single image is presented without caption or explanation, and the purpose is to be humorous, thought-provoking, and bizarre. We’re used to this style of art being utterly mainstream now—think about everything from The New Yorker’s comics to the wackier panels of The Far Side—but in France in the ’60s it was developing as an expression of political and social subversion.

In 1962 Topor teamed up with Fernando Arrabal and Alejandro Jodorowsky to form the art group Panic Movement, a collective that put together provocative performance art pieces inspired by the work of Surrealists such as Antonin Artaud and Luis Buñuel. Topor was also one of the artists who worked regularly with the anti-establishment magazine Hara-Kiri (the “Stupid and Nasty Newspaper,” according to its own proud subtitle), which was published throughout the ’60s until its satire of the death of Charles de Gaulle in 1970 led to it being banned by the French government. (The people behind Hara-Kiri immediately turned around to start Charlie Hebdo, which has been a lightning rod for conversations about freedom of the press since the deadly 2015 terrorist attack on its offices in Paris.)

While Topor’s first published illustrations may have appeared in counterculture French magazines, his work definitely didn’t stay there. Throughout his career, his illustrations spread into more mainstream and international outlets; his drawings appeared in everything from Elle to The New York Times to reinterpretations of Alice in Wonderland and Cinderella (but not the sort of reinterpretations that were suitable for children). Even when the publications were more mainstream, Topor’s art remained aggressively bizarre. Throughout his life, his work was always provocative, often a bit gross, and ruthlessly tongue-in-cheek.

He was also an author and playwright, although little of his work has been translated for audiences outside of France. The most famous of his written works is the novel The Tenant, which was adapted into a film of the same name by Roman Polanski in 1976. He also did a bit of acting himself, playing Renfield in Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979).

In every medium, in any art form, Topor was deliberately pushing boundaries, causing offense, and challenging norms. About his own work, he once said, “I want my existence to be a supreme affront to the vultures who have become so impatient since the forties, by way of an uninhibited representation of blood, shit and sex.”

I offer this mini biography of a very interesting artist for two reasons. The first is that “a supreme affront to the vultures” is a hell of a goal for an artist, and it’s one that I can’t help but admire.

The second reason is that as soon as I finished watching Fantastic Planet, my immediate thought was, “What the fuck did I just watch?”

Now, I don’t think that’s a bad reaction to have. We’ve all had that reaction to movies, and when it happens we have a choice to either embrace it or shy away from it. I don’t think it does us as individuals or as a society much good to shy away from that reaction without examining it. In fact, I love when a film makes me think that, because my next thought is inevitably, “And where the hell did it come from?”

At some point during the ’60s, Topor began working with French animator and director René Laloux on an adaption of the 1957 novel Oms en série (Oms Linked Together) by science fiction writer Stefan Wul. “Stefan Wul” is the pen name of Pierre Pairault, a French dental surgeon who spent his free time writing sci fi novels. Lalouz and Topor had collaborated before, when they were both very new to animation; they worked together on the short films Les Temps Morts (Dead Times) (1964) and Les Escargots (The Snails) (1965), the latter of which is about an invasion of giant snails. These films aren’t great, in spite of the giant snails, although there are elements of the grim weirdness Laloux and Topor would later embrace in Fantastic Planet, as well as a rougher version of the same cutout animation style.

Let’s talk about that animation style for a moment. Cutout animation is a type of stop-motion animation that involves the manipulation of two-dimensional drawings, shapes, and images. I could explain that in more detail, but I’d rather let Terry Gilliam do it in an educational video from 1974. Gilliam’s iconic Monty Python animations are among the most well-known examples of cutout animation; he used collage cutouts from existing media, but that’s just one way to go about it. Another way is to use images created from single-color paper, which brings us to the other most well-known example of cutout animation: “Cartman Gets an Anal Probe,” the infamous pilot episode of South Park (1997), which launched so much cultural pearl-clutching in American media and also meant that I (and all other Coloradans) had to spent a significant amount of time in the late ’90s explaining to people that, yes, South Park is a real place but, no, it’s not like that. All of South Park after the pilot episode has been created using computer animation to simulate the cutout style, but the first episode was made the old-fashioned way, with overhead camera shots of scenes made of construction paper and glue.

But cutout animation had a long, long history before the likes of Monty Python and South Park. An early example from the Soviet Union was China in Flames (1925), a propaganda film (encouraging Soviet support for China against imperialist western influences) with a beautiful, interesting art style. (I’ll talk about Soviet animation in more depth with next week’s film.) Elsewhere during the 1920s, one of the most influential animators of all time was hard at work in Berlin. Lotte Reiniger’s stunningly beautiful silhouette animations, many based on fairy tales and folklore, remain iconic to this day. Her film The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926) is generally thought to be the oldest surviving animated feature film. It’s not the oldest known animated feature, however, as that honor goes to Argentinian director Quirino Cristiani’s satirical cutout animation film El Apóstol (1917), which has unfortunately been lost to history. Because the film is lost, it’s harder to find images from it online, but those that do exist show comics-style drawings that were cut out and articulated for apparent motion.

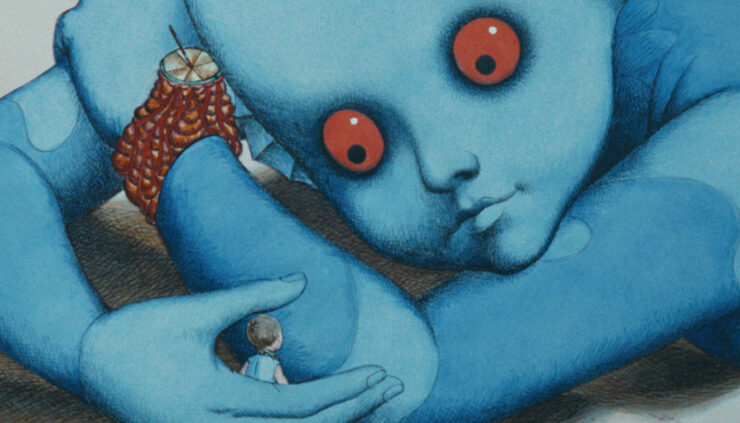

Fantastic Planet is another variation on cutout animation, one that follows the same general form but isn’t quite like any of those others. The film was illustrated and animated over the course of about four years at the Jiří Trnka Studio in Prague. The art, which was designed and overseen by Topor but also involved a large crew of artists and animators, consists of gorgeous, detailed, colorful pencil drawings. The film’s sense of motion is created using clever camera cuts, zooms, and rotation. It’s well done and surprisingly immersive, for all that both the art and the animation style make no attempt at realism. I never found myself thrown out of the story by a sense of falseness. The style is odd, to be sure, but so is the story and the world it represents.

Which brings us to the obvious question: What does it represent?

The answer: It depends on who you ask. It depends on whether you are searching for a single unifying allegory, or view the film as containing elements of several themes.

That the film is a political allegory is not in question. It’s not subtle. It’s not trying to be anything else. It’s about giant blue aliens who keep humans as pets and the humans’ long struggle to escape oppression and secure their freedom. That makes it the kind of political fable that can be and has been interpreted to mean any number of things and tied to any number of historical or movements. I don’t know what Wul had to say about his novel; digging into French sci fi from the ’50s is not an easy task for somebody who doesn’t know French, and most of the English-language criticism focuses on the film. From what I can tell, neither Laloux or Topor ever offered a specific interpretation. That leaves it to the viewers, and over the decades viewers have had quite a lot to say.

The film went into production in Prague right before protests of the Prague Spring were stop by the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, after which film production was temporarily halted so that all movies might be assessed for subversive messages. Of course, Fantastic Planet is full of subversive messages, but perhaps the fact that they were French subversive messages couched in surreal weirdness helped it slip by the Soviet censors, or maybe it was simply the economic boon of an international co-production that let it pass. In any case, the people working on the film would have needed to look no farther than their own lives and work to see the effects of oppressive authoritarianism in real time, which might go some way to explain why the film is so generally political without being specifically political about identifiable events.

For one thing, Fantastic Planet is full of elements and images that suggest an anti-racist and anti-colonialist reading. This is particularly apparent in the scenes when the young Om Terr (voiced by Eric Baugin in youth and Jean Valmont as the older narrator) is living in the Draag home with Tiwa (Jennifer Drake). The restrictive collar, the forced costumes, the prohibition against learning, the condescension about what Terr might understand—these are all elements that fit with a parable about slavery and colonialism. Critics have linked it to everything from the Civil Rights movement in the U.S. to the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa to the Algerian fight for independence from France.

At the same time, modern critics also see a pretty straightforward animal rights message in the film. I understand where that interpretation comes from, because the film is asking the audience to imagine ourselves as mistreated animals. But I find it rather unconvincing. A significant component of the story is the way the Draags deliberately ignore and deny the fact that the Om have intelligence, language, and culture of their own. That to me feels a lot more like a metaphor for violent and systemic dehumanization, one that is using the language and imagery of humanity’s relationship with animals to comment on humanity’s relationship with itself. (I reserve the right to change my mind if my cats start sneaking away to build rockets.)

Then there is the most harrowing scene in the film: the extermination of the Om in the park. The Om are confined to a limited area, an unused corner of the Draag neighborhood, a walled ghetto—but even that does not satisfy the Draag. It isn’t enough that they capture, confine, train, and punish the Om; they don’t want any living free, even in a place that nobody else is using. So they regularly enter the park to kill the Om with poisonous gas. For the Draag, it’s an unremarkable part of life. For the Om, it’s a repeated and ongoing horror. It impossible to watch that long, agonizing scene without thinking of the Holocaust.

I’ve never seen anything quite like Fantastic Planet, because there isn’t anything quite like it. I enjoyed it immensely, even though I also found it very upsetting. The allegories are likely drawn from several places, all of them grim reflections of human history, but the specifics of this story are singularly weird and the art used to convey them even more so.

I’m not quite sure what I was expecting, as I try not to read much about the films that are new to me before I watch them. That’s part of the joy of watching a wide variety of movies with an open mind and genuine curiosity. But I know I wasn’t expecting that grooving acid jazz soundtrack. I wasn’t expecting the abundance of unnerving flora and fauna on this fictional planet. I was definitely not expecting the enormous moon statues and their cosmic psychic mating dance. Nobody is ever expecting that.

Even though it’s considered a cult classic and remains an artistic favorite among cinephiles and animation fans, Fantastic Planet is not movie that anybody has ever really tried to emulate or copy. That in itself is interesting. It’s instantly recognizable and truly unique, with very few films out there that we can even compare it to, and that’s something we don’t see all that often in the history of sci fi cinema.

What do you think of Fantastic Planet? What are your thoughts on its political allegories? Which of the plant-things on the planet provides you with the most nightmare fuel?

Next week: We’re all going to be curious Soviet schoolchildren for a while and watch Mystery of the Third Planet. You can find it on YouTube and the Internet Archive.

Thank you for putting this into context.

I saw this a couple of times on late night tv when I was a kid. I’m ancient, so I was like, 9-10-11yo, somewhere in that neighborhood. I associate it with Don Kirshner’s Rock Concerts, which were a post-11pm, Friday/Saturday night type of deal.

I was already into SFF by then, and clearly saw the oppression, etc. It is a deeply unsettling film…and as a black person, the allegory of Oppression is so obvious I don’t see how people could miss it, even if the basis is rooted in the Holocaust.

Honestly, I’m not sure what else to say about it. It’s been years since I’ve seen it and I have no desire to do so again. The art is fantastic, as is the animation. Admittedly, to my modern eyes, the links to his provocative are are…something. Very French, very Male, very of the time period.

This was the Flying Dutchman of animated fantasy films of the seventies: mysteriously appearing at the odd local theaters for brief showings in the early part of the decade (complete with adds on local television stations) then disappearing for a few years only to haunt the midnight movies and college film guild scene at decade’s end.

It made an appropriate companion film to the low budget live action science fiction movies of the time like “Soylent Green,” “Silent Running” and “ZPG” while also being a perfect example of how much more artful and fascinating the independent animation scene was at the time-at once crude and messy but frequently brilliant and deeply affecting in a way Pixar films can never be. It also much more effectively captures the “Heavy Metal” vibe than the actual licensed film adaptation came remotely close to.

Well worth seeking out.

I first watched this movie on a rented VHS tape. It has the odd quality, to me, of refusing to stick in my memory. The brief scene with the creepy critter in the cage that starts at about 1:20 in the trailer was the only piece of the entire thing that I could recall as more than a disconnected image or a theme. I think I have seen it three or four times since the days of mom’n’pop video shops, and every time it slips away again.

My dad took us to see this at a rep house when we were far too young. In retrospect I’m pretty sure he thought we were going to see Forbidden Planet.

I’ve watched ‘Fantastic Planet’ a few times thanks to working in animation / VFX for much of my adult life. Everyone I’ve spoken to about this film has the same reaction – “what the hell was that all about? that was out there?” – and artists in particular are often very enthusiastic about it given the technological limitations of the production. The strong emotional connection felt by viewers is a recurring theme. On that basis alone ‘Fantastic Planet’ deserves its status as a cult classic.

For me the film is about humanity, just like all good SF. More than once I’ve ventured the opinion that the blue aliens are actually a metaphor for the wealthy who dehumanize the masses. The dehumanisation aspect also mirrors WWII and Fascism, extreme capitalism (topical at this moment), communism or any other -ism you care to project. Humanity is, however, very much at the core of this film.

As for the flora and fauna and everything else? On a more recent viewing I wondered aloud if one of the key parties (director, writer or similar) was undiagnosed ASD, had suffered a psychotic break or consumed far too much psilocybin. The sense of disconnection and unreality is palpable and the weirdness is the stuff of abnormality.

Most important question is… do you like ‘Fantastic Planet’? On balance I’d say I do but I find the emotional aspect hard going. A comfort movie it is not.

I remember catching this at a theater back in the early ’70s. I also was WTF at the end. I did enjoy it, but floundered to explain it to my wife, or even myself. There are movies, and even books, that affect me even without my understanding them at some level below, or maybe above, verbalization. Now, when I see reference to it I’m reminded of the Voynich Manuscript. Pretty pictures, but some kind of context is missing. Sure, I did get the points mentioned: slavery, animal abuse, and dehumanization. (Is it dehumanizing if it’s an alien doing it?) Anyway, I’ve certainly never forgotten the experience!

I have nothing profound to add, just this: Kali, I’m glad that you covered FP and that you enjoyed it.